I love that I live in this age of planet discovery. In 1992, the first planet (or dwarf planet, minor planet, or Trans-Neptunian Object) in Pluto's neighborhood (besides Pluto itself, discovered in 1930) was discovered, and since then there are now more than 1200 on record, including Eris, Makemake, Haumea, Sedna, Orcus, and Quaoar.

Love those names.

Outside our solar system, planets are being discovered at record speeds by the orbiting Kepler telescope, which is watching about 150,000 stars and waiting for the amount of light they give off to dip. The dip could be for a variety of reasons, but if it dips again, there might be a planet passing by in its orbit. And if the light dips again, after the same amount of time has passed, you've found a planet for sure. And if you know how big and bright the star is (which you can determine from its light spectra), you know how much light the planet is blocking, and therefore how big it is.

Some of the first planets discovered outside our solar system were discovered with similar techniques. Watch a star, see if it dims, and see if it dims with regularity. The other method involved careful measurements of the stars position, and seeing if it moved side to side with regularity. That would indicate a planet's pull on its star, tugging it around as it orbits. Both methods began rudimentarily, only detecting the biggest gas giants orbiting closer to their suns than Mercury to ours. These are commonly known as "sun-grazers." And when you're looking for Earth-like planets, you have to keep looking.

This is all prelude to the big news. So far, Kepler (the satellite, not the long-dead astronomer) has discovered 708 confirmed planets (at least three passes) and over 2,000 planet candidates (only two passes so far). These results were announced yesterday, and one of those 708 confirmed planets had some interesting features...

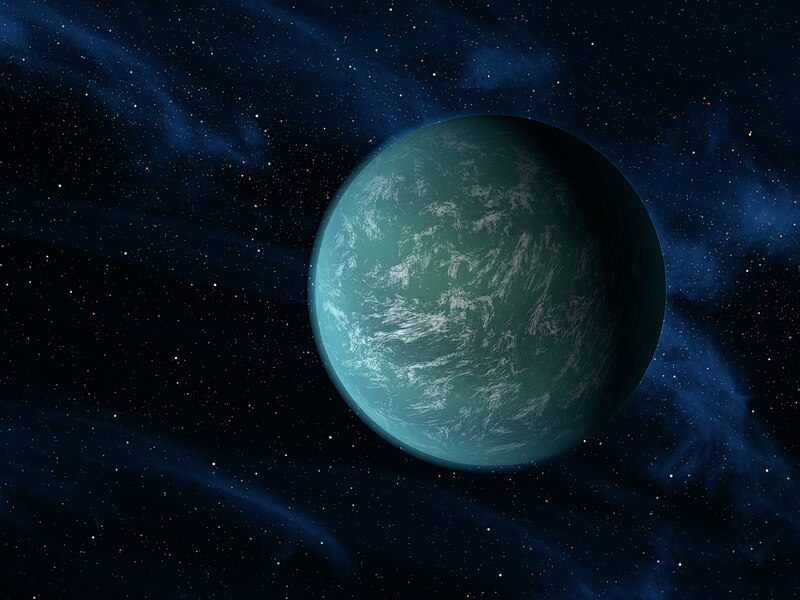

"Kepler 22-b: Earth-like planet confirmed"

Wow! But hang on a sec. It's so easy to see the phrase "Earth-like" and think of our little blue planet, a small ball of rock, covered in air and water, teeming with life. But exactly how Earth-like is this new planet? Well, looking at the facts tells you some pretty exciting things. This new planet is bigger than Earth, but it's no Jupiter. If you were on the surface, the extra gravity would make it more difficult to walk around, but it wouldn't kill you. So the size is essentially Earth-like, yes. And it's in the habitable zone of its star: not too hot, not too cold. We think the surface temperature might average around 22ºC, which is about room temperature. Cozy, right?

Of course, after reading the article, and again after reading Phil Plait's take on it, I do have an issue with the word "Earth-like." It was worse on the link to the article, which read: "Astronomers confirm 'Earth twin." Twin? Look, it's a neat discovery, but it's far too soon to be calling this planet a twin.

Here's what we don't know, and why we can't jump on the "twin" and "Earth-like" bandwagon just yet: we don't know yet what this planet is made of! Solid, liquid, gas? We don't know. As Phil Plait pointed out, we don't even know if it has an atmosphere (although based on its size alone I'm guessing it probably has one of some sort). If it's solid, like Earth, that would be incredible, especially if water was confirmed, since at the known temperature, water would be liquid, which is just what's needed for life on Earth. And all- or nearly all-liquid planet would still be neat, and again, if that liquid was water, this planet could have life swimming around its planet-wide oceans.

If the planet is mainly made of gas, which I honestly don't know how likely that could be, would be a bummer. Gas giants like Jupiter and Saturn seem extremely inhospitable. I don't know how small gaseous planets can be, but in our solar system, the four we have are many times larger than Earth. If this new planet is made of gas, maybe it has an extremely dense core of some sort to keep it all together in a relatively small space. At this point, nobody really knows.

If we do find out it's made of rocks and water, keep in mind this planet is 600 lightyears away, which means it would take a beam of light 600 years to reach it from here. The farthest humans have ever launched anything from Earth was the Voyager 1 probe, currently at 0.0019 lightyears, and it's taken 34 years to get that far.

Again, I'm excited. I love news like this. I hope we do find a planet just like ours, with cool breezes on sandy beaches. But we haven't found it yet, or at least we don't know yet for sure. And we'll have some work to do if we're planning a trip.

Just heard for first time the other night the term, "Goldilocks planet" - not too hot, not too cold - have you heard that yet? In the conversation folks were referring to "this Goldilocks" and "that Goldilocks." And I was confused. But not after I got the explanation.

ReplyDelete-Cirrelda

As someone who's been following extra-solar planet discovery for several years now, yes, I've heard the term. My favorite part about it is, technically, Earth, Mars, and Venus are all in the Goldilocks zone of our sun. But Venus is on the warmest edge, and has an atmosphere so thick it absorbs a lot more of the energy it gets from the Sun, and Mars is on the coldest edge, and has an atmosphere so thin it can hardly keep any energy from the sun at all! Now imagine if they changed places, both planets could have ended up with friendlier atmospheres, and liquid water on the surface.

ReplyDeleteSo finding a planet our size and in the Goldilocks zone is very cool, but the atmosphere can really make or break it.