(The above is one of the many downsides to always wanting to be technically correct, but I'm going to get back on track now.)

"Only a theory" is pretty much the same as saying "only everything we know." A theory, despite the colloquial definition, is not just some idea you had lying awake at night. Theories are amassed from vast amounts of information, all pieced together into one model that explains everything. And I mean everything.

If you look at the theory of gravity, or universal gravitation, the reason it was so amazing was that it connected the rules governing objects falling toward the Earth, and the rules governing the orbits of planets around the sun. Nobody before Newton had ever connected those two phenomena, but many had tried to explain one or the other separately. The problem was, without looking at the whole picture, a satisfactory answer was impossible.

So, let's be clear right now. In scientific terms, a theory is a model that explains all the information we have, but is impossible to directly observe. A hypothesis is an untested idea that, through research or experimentation, could be proved, disproved, or become a theory of its own (if it fits all the data yet is impossible to directly observe). A hypothesis that does not fit the data is discarded, and a hypothesis that fits some of the data, but not all of it, is probably waiting for a better one to come around.

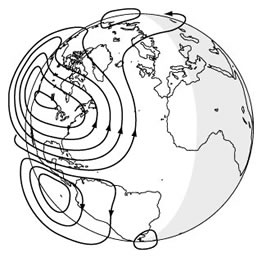

A current model of atmospheric electric currents.

An outdated model of atmospheric electric currents.

Now, to the average English-speaking person, "theory" and "hypothesis" mean pretty much the same thing. They're both untested ideas. And I honestly don't have an issue with popular ideas changing how words are used. It makes for a growing, evolving language. In this case, I think it's up to scientists to choose their words with care when expressing scientific ideas, and understand that if they use the word "theory," they should explain exactly what they mean, even if it sounds redundant to their own ears.

Here's an example of my favorite "theory" (which is actually a thoroughly disproved hypothesis) which two people in my life have tried to convince me is true and is being covered up by scientists, the media, and Google maps: Hollow Earth.

Wait, wait, I'm not sure you read that correctly in that big block of text, so I'll separate it out and tell you again, slowly:

Hollow. Earth.

And yes, the idea is exactly what it sounds like. There are a few variations, but essentially the idea is that there is a vast hollow space under the Earth's crust. Sometimes there are several layers, several different hollow spheres, one inside the next, like nesting Matryoshka dolls. Sometimes there is a tiny "star" at the center to light and heat the surface underneath. Sometimes you can walk on the underside, sometimes the next sphere down is your surface. Often the idea includes two holes leading to the hollow core at the North and South poles.

Image credit: Rick Manning

Image credit: Rick Manning

One version of Hollow Earth states that we are on the inside, looking to the core whenever we look up at the sky, and that distance increases to infinity as you approach it. Although this version is more of a thought experiment than anything else.

Image credit: Joshua Cesa

These ideas can be found in works like Dante's Inferno, which describes nine layers of Hell, with Satan frozen at the center of the Earth. Jules Verne's Journey to the Center of the Earth describes a similar journey, though the adventures only go about one layer deep, so it isn't clear if the true center is hollow or not.

But Hollow Earth, whatever version of it you like best, is thoroughly disproved. It has never been a theory, merely an idea proposed by ancient people, and drummed up again by some scientists and pseudo-intellectuals in the past few centuries to explain some evidence, but not all of it, or to sell books.

Let's look at some of the most glaring problems with Hollow Earth.

1. Planet formation. Imagine you're baking a cake, and you're putting the ingredients together. You need to put six cups of flour into a large mixing bowl. Imagine pouring the flour not into the center of the bowl, but instead around the sides, letting the flour slide down to the center. When you're done, you should have a pile of flour in the center of the bowl, probably higher around the edges. But look in the exact center, and there is bound to be some flour there as well. Hollow Earth demands that the bottom of the center of the bowl remain devoid of flour during this process, and with a smooth, rounded bowl, that is essentially impossible.

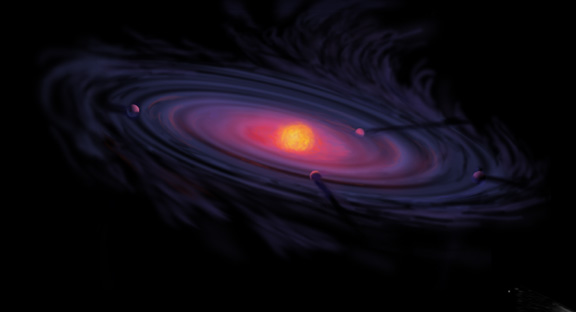

This is a very rough model of how planets are formed. We know from testing rocks from Earth, Mars, and our moon, from detecting amounts of helium and hydrogen in the sun, and from observing the orbits of the planets, how and when the sun and planets came to be. All the data points to everything beginning as a spinning dust cloud, with the majority of the dust ending up as a star, our sun, and the rest coming together as mini spinning dust clouds forming the planets and moons or remaining as bits of debris like comets and asteroids.

Now that's some handsome science.

So every planet, moon, and even the sun began as a vast cloud of dust (flour) pulled together to its center of gravity (the bottom of the bowl). And you could run the scenario a million times over and never get one planet that forms with a significant hollow space in the middle. Rock, on the planetary level, is very much the same as the flour in the bowl, and it will fill up the space at the bottom.

2. Physics. Let's suppose, though, that the Earth was hollow. How stable would it be? We know, for instance, that the Earth's crust is about as thick, relatively, as an apple's skin. Again, I'll ask you to imagine that bowl of flour. Working with just the dry flour, do you think you could shape the flour into a hollow sphere, with the thickness of an apple's skin? Not without some underlying support, be it additional material or an outside force, would that flour stay up on its own. It would always crash down and fill up the empty space.

The thickness of the crust here has probably been exaggerated.

On a planetary scale, no known force or material could possibly support the weight of the Earth's crust with a hollow space underneath. The rock under our feet is like so much flour on that scale. Line the inside with titanium, put a powerful magnetic force at the center, it wouldn't matter. The Earth is just too big for any natural force to support the crust on its own, aside from a completely filled-up core, which churns with heat and energy under the pressure.

3. Observation. The Hollow Earth hypothesis was certainly intriguing and could have been very convincing to ancient people. I can even see why people might take it as a serious idea up into the 19th century. But we have a huge amount of evidence now that tells us Hollow Earth isn't true.

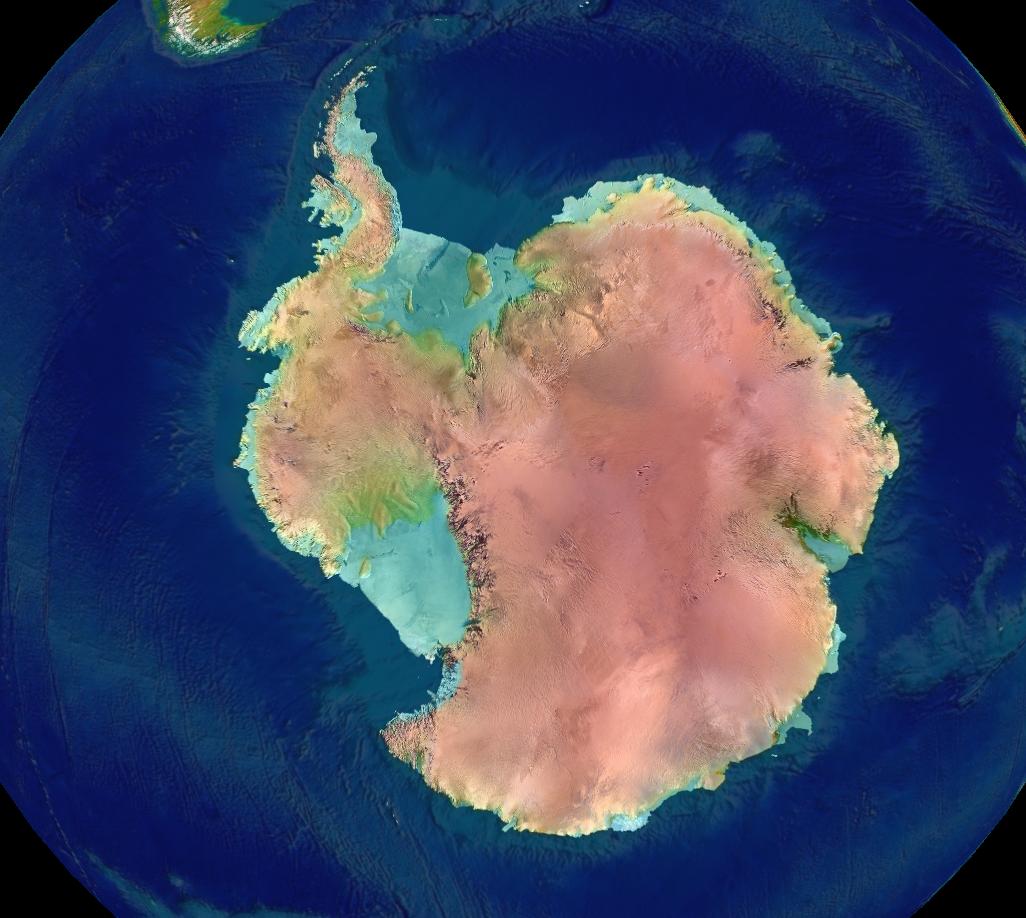

We've been to the poles, and made maps with satellites that can see under the ice, and there aren't any holes to the hollow core.

Point to the hole to Earth's core.

We measure earthquakes all around the world, and can connect the dots to show that earthquake waves move through the core in a way that would be impossible if it was made of anything other than molten rock and iron.

That iron core is also the only explanation for the Earth's magnetic field, which is itself the only reason we have auroras in the northern and southern skies, and why compasses work (and why we aren't fried by the cosmic rays from the sun).

And tectonic activity (the movement of the plates of Earth's crust) shows that continents have moved over time, which means they must be resting on something.

And we know how much mass the Earth has based on its gravitational pull, and the majority of the mass is missing if you take out the core.

Hollow Earth believers can try to explain away these phenomena with more ideas that fit the framework of a hollow Earth, but only in response to new evidence that refutes it. A bad model has to have more and more parts added on to explain away evidence, but a good model predicts the evidence. A bad model is based on some data, but a good model encompasses all the data.

Hollow Earth is a bad model. Universal gravitation, solar system formation, and "Core Theory," as a Hollow Earth believer once put it to me (I died a little inside that day), are all good models that encompass all the data, and predict evidence before it is found.

In science, a theory is like a ship. One hole won't bring it down, and can often be an opportunity to add something new, but if there are as many holes as planks, you're better off on another boat.

Note: all uncredited images are in the public domain in the United States.

Thank you for interesting discussion here. Yeah, you would think folks who ally themselves with an idea would be more familiar with the whole testing hypothesis mode - and start going down the list of possible tests from everyday life ... like your cake mixing in a bowl analogy.

ReplyDelete-Cirrelda